That Will Be England Gone : the Last Summer of Cricket / by Michael Henderson : Constable, 2020.

Speaking of things that can easily be confused (A Waft of Pre-War Cigarette Smoke), some people may not be receiving quite the Christmas present that they were hoping for this year. ‘Any ideas for Dad? He did mention a cricket book – think the author’s name began with an ‘H’ and ended in ‘on’. Apparently the author thinks that ‘The Hundred’ means the end of traditional cricket, so he travelled round the country, watching games at various grounds, before the whole thing disappears. I can’t imagine there’s more than one of them!’.

It was probably a mistake to read Henderson’s book immediately after finishing Duncan Hamilton’s ‘One Long and Beautiful Summer’. A sense of déjà vu creeps in as early as the second paragraph, where Henderson quotes Cardus’s ‘There can be no summer in England without cricket’, whereas in Hamilton’s antepenultimate paragraph he had quoted him as saying ‘There can be no summer in this land without cricket’ (Hamilton’s version appears to be the accurate one). Hamilton is, incidentally, credited as one of eleven ‘readers’ of Henderson’s work : none of them, apparently, ‘fact-checkers’.

Henderson might easily have transplanted Hamilton’s subtitle (‘an elegy for red-ball cricket’) on to his own title. If there were any doubt that he intends it to be an elegy, he cleared that up in a testy letter to ‘The Cricketer’, taking issue with Ivo Tennant’s review, which had described his book as ‘near-elegiac’ : ‘there’s no near about it’ responded Henderson. However, whereas Hamilton devotes his elegy to cricket, Henderson’s takes in the whole of English culture : a better title might have been ‘England : an Elegy’, had that not been taken by Roger Scruton.

Both Hamilton and Henderson cover much of the same ground, and some of the same grounds (there seems to be a prescribed itinerary for this evolving genre) : Lord’s, Grace Road, and (for the same games) Trent Bridge, Scarborough, and Taunton. Both admire Philip Larkin : Hamilton regrets that he never wrote a poem explicitly about cricket ; Henderson takes his title from ‘Going, Going’ and his chapter headings from other poems. Hamilton captures some of the spirit of Larkin’s poetry ; at his best, Henderson achieves something of the qualities of his journalism (at his occasional worst, he can resemble the Larkin of his less appealing letters).

In spite of the similarities, these are very different books. Henderson lacks Hamilton’s descriptive gifts : he is a polemical writer, whose stock-in-trade is the short, provocative, column. His descriptions of the games that he saw tend to be perfunctory, and exist primarily as a pretext for delivering a self-contained essay (his visit to Ramsbottom, for instance, is a pretext for an essay about Lancashire). Hamilton shows ; Henderson tells, and frequently tells off. If Henderson were a guest at Christmas dinner, he would be a bachelor relation of a certain age who always brings a couple of bottles of something decent, has a fund of good stories (some of them new), but who tends to monopolise the conversation, and has a tendency to upset the younger members of the family with his opinions.

Hamilton’s method (following Blunden) may be digressive, but his digressions rarely lead the reader far beyond cricket. Henderson, taking as his justification his own (accurate) observation that watching cricket offers ‘every minute … opportunities for digression and diversion’, digresses so far that prospective purchasers, lured in by the photograph of cricketers on the cover, may well feel that they have been sold the book under false pretences. (What do they know of cricket who only cricket know? Well, they presumably know a lot about cricket.) He has written, perhaps apprehensive that he might not get another shot at it, at least three books in one : a cricket book ; an autobiography ; and a study in Arnoldian cultural pessimism (though he tends to be closer to Wallace Arnold* than Matthew).

Anyone undecided as to whether this is the book for them would get a pretty good idea from a flick through the introduction (titled, with a nod to Cardus, ‘Prelude’). Proust makes his entrance, neither irrelevantly nor entirely necessarily, in the third paragraph, to be followed by, in the first seven pages : Yeats, Orwell, Forster, MacNeice, Thomas (Dylan), Rattigan, Chekhov, Beckett, Pinter, Joyce and Stoppard. Henderson does not so much drop names as pelt the reader with them, less, I suspect, to impress readers familiar with these writers than to annoy those who are not. The first of his many ‘old chums and quaffing partners’ turns out to be John Arlott, who imparted some words of wisdom to Henderson while ‘pouring wines from Spain at The Vines, his home in Alderney’.

Explaining why he is unlikely to appreciate ‘The Hundred’, Henderson writes ‘I have no interest in social media, have never bought a lottery ticket, and wouldn’t watch a ‘reality’ show on the television if I were granted the keys to the Exchequer’ (an echo of Hamilton, who also writes that ‘The Hundred’ is likely to appeal to people who use Twitter and watch ‘Reality TV’ (dread phrase!)). Having asserted that ‘there are more small-c conservatives, of left and right, about than modern tastemakers suppose’ (which I think is true of the world of cricket – we tend to be most conservative about the things that mean the most to us), he goes on to quote Michael Oakeshott’s classic description of the spirit of conservatism from 1956. At which point, I imagine, readers who are allergic to any taint of conservatism, and run away at the first whiff of Oakeshott, will shut the book with a bang and a sigh, and look for something else to read, which would be a pity.

I imagine a few more cricket-hungry readers may have been shed by the end of the first chapter. The only time I stayed in Malvern, it was as a base for a visit to New Road, Worcester, but that is not why Henderson is there. Instead, he climbs the Beacon and gives us a literal tour d’horizon (I am surprised that you can see as far as Birmingham, but apparently you can). This leads on to an essay on the nature of the English national mythology (which seems to have been designed specifically to be ‘deconstructed’ (i.e. not deconstructed) by some earnest young academic), and then, by a circuitous route, to a reminiscence of his time at Prep School, where, at last, he was introduced to cricket. Like many writers noted for vituperation, he is more interesting when writing about things that he likes, and he writes well, and endearingly, here about his childhood heroes (chief among them, as a Lancastrian and a wicket-keeper, Farokh Engineer).

After a (metaphorical) tour d’horizon of the state of English cricket, we come to a chapter entitled ‘New Eyes Each Year : Trent Bridge’, which, eschewing the obvious approach, begins with an extended tour of the topographies, histories and cultures of Vienna and Berlin (I think he quite fancies himself as Karl Kraus, ‘whose essays goaded polite society’). This is quite useful, in a ‘Rough Guide’ kind of way, and, though some will find it trying, is not entirely gratuitous (his point is that people, like nations, have a personal mythology, and these places are part of his, as is Trent Bridge). He writes well about his favourite Test ground, though not as well as Hamilton, has some more warm recollections of heroes of the past (like Hamilton, he idolised Sobers), and has pertinent things to say about matters arising, but there is little in the way of description of the game he went there to see (the first of the season, against Yorkshire) ; like a dog distracted by a long-buried bone, he wastes time aiming a few kicks at the long-gone backside of an old bête noir, Kevin Pietersen.

Anyone not alienated by now might be tempted to bale out before the next stop on our journey, at Henderson’s old Public School, Repton, where, led, improbably, by a lad named Berlusconi, the XI were taking on Uppingham. He takes this as a pretext for an essay on ‘What I Think about Public Schools’, a subject which, for some, never palls.

As far as I know, Henderson did not go to University, otherwise we might be off to The Parks. Instead, we find ourselves in Ramsbottom, not far from his home-town of Bolton, which seems to bring out the best in him. I enjoyed being reminded that ‘Sooty and Sweep’ featured a snake called Ramsbottom. I liked the anecdote about Tom Finney and Nat Lofthouse playing a benefit match in Grimsby, and being paid in fish and chips (‘I got cod and Tommy got haddock’, commented Lofthouse ‘which was only fair – he was the better player!’). Previously unknown to me, the comedian Albert Modley (catchphrase ‘In’t it grand when you’re daft?’) sounds like he might be up my street. I was intrigued to lean that BBC employees, decanted to Salford, have migrated to Ramsbottom, and turned it into a little Islington (allowing him to make a few cracks about the much-hated avocado). He has even managed to find an amusing story involving Bernard Manning : ‘‘Anybody can tell a dirty joke’ Esther Rantzen told him one night on Parkinson, her face a bag of spanners. ‘All right,’ he replied, ‘let’s hear you.’’

The variety of cultural reference at work is indicated by two contrasting encounters with ‘old chums and quaffing partners’, in the Arnoldian sense : one with John Tomlinson, the Wagnerian bass, ‘after a performance of Die Walküre at the Bavarian State Opera in Munich … we popped into an Italian restaurant off the Maximilianstrasse to celebrate his birthday’ ; the other with Ken Dodd, who tells him that he was never a ‘stand-up’ comedian, ‘one night in Eastbourne over fish and chips’. The only time the eyes start to glaze over, and – if he were a guest at Christmas dinner – you might feel tempted to steer him back to the subject of his favourite comedians, is when he gets on to the subject of Rochdale, and its ‘grooming’ scandals.

He writes at greater length than usual about the match he attends (versus Clitheroe), appreciatively about the teas (a pie, mushy peas, and a pudding for £3.50, and no avocado), admiringly about the contribution made by West Indian professionals to League cricket (particularly Learie Constantine), and sympathetically about the plight of those seeking to keep the League tradition alive.

The next stop on the magical mystery tour is Scarborough, followed by two other outgrounds, Chesterfield and Cheltenham, about which, once you have hacked through a thicket of potted history and irrelevancies, he writes almost as well as Hamilton, even movingly. I was amused to learn that Hitler fantasised about whirling Eva Braun around the ballroom of the Grand Hotel in Scarborough (amusing, if true), groaned inwardly at another diatribe against John Lennon (one of his party pieces, introduced for no good reason), puzzled at his description of Lindsay Anderson as a ‘flaneur’ (I think he means ‘poseur’), but I cannot fault his concluding ‘at each ground the commonwealth of cricket lovers, gathered by bookstalls and ice-cream vans, remembered they were not alone … there are still unnumbered thousands who love cricket in the way people always did’. It is at Chesterfield that Henderson comes closest to being ‘one of us’ (or to being me).

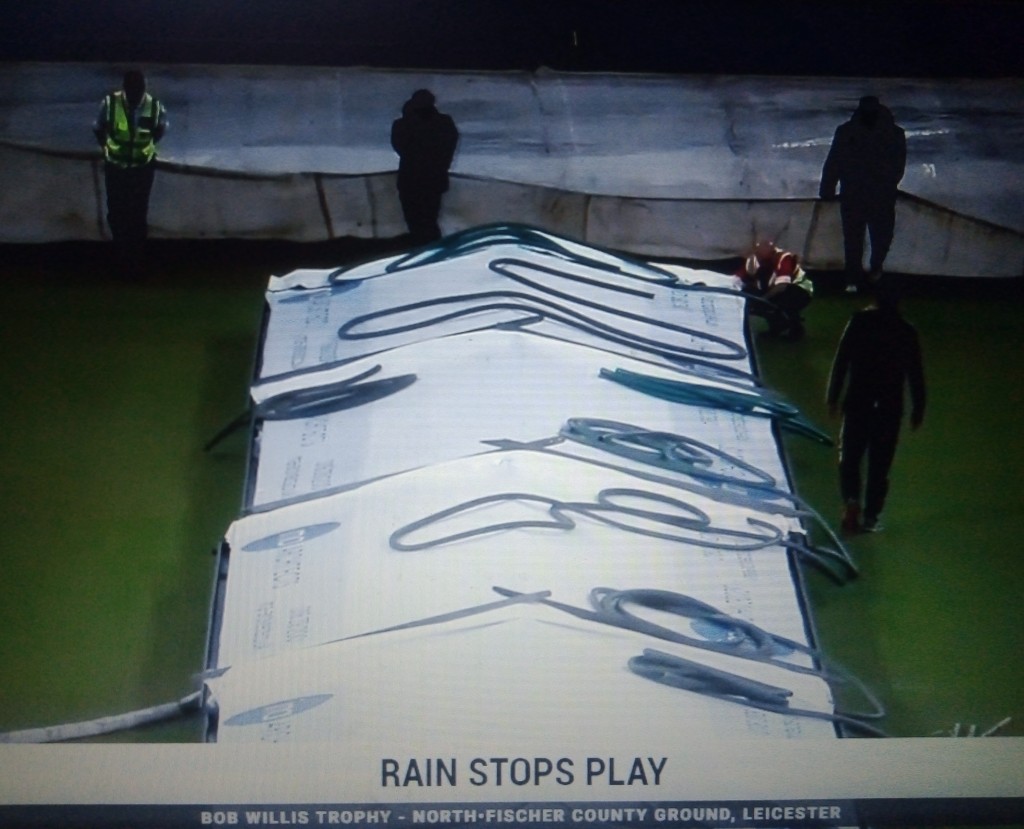

That good impression does not survive his trip to Grace Road (‘twinned with Desolation Row’), about which he writes with the distaste of a Guards officer posted to guard a field latrine. In fairness, I doubt whether I should have been much more enthusiastic about an evening T20, in which Leicestershire were slaughtered by Yorkshire, and I cannot quarrel with his concluding ‘My word, this was boring. And there are five weeks [of T20] to go’ (a sentiment to which this human bosom, at least, returns an echo).

He begins by noting, as all journalist-visitors seem to, that the ground is surrounded by terraced houses : in what were, in some ways, happier days, it was also surrounded by factories ; at a time when most people lived within walking distance of their place of work, the ground would fill up after tea, as the workers made their way home via the cricket. He also describes it as ‘the most functional ground in England’, which is surely a good thing if you are looking for somewhere to watch cricket : Le Corbusier might have described it as ‘a machine for watching cricket in’.

The Meet gets off lightly (‘a large hut’), but he goes on to suggest that ‘if championships were awarded for contributions to care in the community, Leicestershire might have won as many titles as Yorkshire’ (truer than he might realise), and asks ‘Friends of Grace Road : are there four sadder words in cricket?’, which is odd, given that he also says ‘one can only commend the men and women who gather here in the summer months, striving to keep cricket alive …’. If he ever shows his face in the Meet again, I feel that the Friends would be entirely justified in sticking one of their delicious, home-made, triple decker cream cakes right into it.

It does not require any local knowledge to work out that it was Stuart, not his father Chris, Broad who moved from Leicestershire to Nottinghamshire, but it helps to unravel his mysterious claim that the start of play was announced by ‘a blast on a hunting horn, the traditional greeting in this land of red-coats’. They used to do this before the football at Filbert Street, but I have never seen it at Grace Road, and I suspect that what he actually heard was Stench’s vuvuzela (an unlikely huntsman).

At this point, many readers will be tempted to echo the author, and say ‘My word, this is boring. And there are another ninety pages to go’. A reminiscence of his old c. and q-ing p. Robert Tear (the tenor) leads into a summary of his views on various institutions : the BBC, the Church of England, the Globe Theatre, the English National Opera, the Arts Council, the National Trust, Test Match Special, and, eventually, the ECB. Change and decay all around he sees, where simpler (or, possibly, more highly evolved) souls see only change. I happen to be more sympathetic than not to most of his opinions, but there is nothing here that he could not have appeared (and I suspect already has) in an opinion piece in the ‘Mail’ or ‘Telegraph’.

After a necessarily brief stop at the Oval (for a rain-affected T20 that lasted eleven overs, but still provided a ‘more of an authentic cricketing experience’ than his trip to Leicester, apparently), we progress to Lord’s, which finds him at his most Arnoldian. Most of this chapter is about Harold Pinter, who turns out to be another old c.. During the 2007 Test against the West Indies, Henderson recalls, ‘I popped into Pinter’s box’ (he is always popping in and out of someone’s box (the kind you get at the opera, not the abdominal protector)), where he also, quite by chance, runs into ‘Ronnie’ Harwood, Tom Stoppard, Simon Gray and David Hare. Henderson invites Pinter to guess his favourite line in the history of cricket-writing, which, to no-one’s great surprise, turns out by Pinter, H. : ‘That beautiful evening Compton made 70’. Although I am sure that Pinter would have approved his choice of author, even he might have been puzzled by his choice of that particular line.

His love for Pinter is not completely blind. He could, he admits, be ‘confrontational’ : ‘Rowley Leigh, the chef who ran Kensington Place, remembered meeting Pinter in his [own] restaurant, and being told to ‘get out of my fucking way’’. This is straight from the Wallace Arnold playbook, as is his having spent three days of the Test against Australia in Tim Rice’s box with an improbable old chum and q-ing p., Paul Cook, the one-time drummer with the Sex Pistols, and Barry Mason, who wrote ‘Love Grows’ for Edison Lighthouse. He does also, in fairness, devote a couple of paragraphs to Steve Smith and Jofra Archer.

Entering the home straight, we find ourselves in Canterbury, but, before arriving at the ground, we have to listen to a potted history of the city, of the kind which you might expect to hear over the tannoy on an open-topped tourist bus (interesting if you have never heard of St. Augustine, Thomas Becket, or Geoffrey Chaucer). I can forgive him a lot for (correctly) describing Powell and Pressburger’s ‘A Canterbury Tale’ as ‘a masterpiece’, and have no objection to his survey of other refugees from Mitteleuropa who enriched English cultural life, but, by the end of a lengthy anecdote about a performance of Mahler’s Sixth by the Berlin Philharmonic, conducted by Simon Rattle (the link being that Rattle’s father was at school in Canterbury, and once faced ‘Tich’ Freeman), even the Sainted Beckett would be tempted to yell ‘Get on with it, man!’. Likewise, when he has seen a game in which 26 wickets fell in a day, it is an odd decision to devote most of the chapter to a history of Kent cricket which will only interest those who have not heard of Cowdrey, Underwood or Knott.

Almost finally, to Old Trafford, his home ground as a child. He has some sympathy for the (then) plight of Haseeb Hameed, and warm words for John Barbirolli, the critic Michael Kennedy and Ian Botham (who, he says, should be awarded a ‘baronetcy’**), but none for the contemporary culture of his birthplace, or the ground. Oasis ‘specialised in rancid stupidity’, Tony Wilson was the ‘regimental goat’ of the city’s ‘youth culture’, and Shaun Ryder (unnamed) appears as ‘a drug-addled pop singer’. If he went to Old Trafford to see a game, he does not describe it, but shakes its dust from his feet with the resonant ‘the ground that meant everything to me has been cleared. The feelings I thought would last forever have evaporated. … I take one last look and leave, through the door marked nevermore that was not there before’***.

And so, to Taunton, where Henderson and Hamilton’s paths meet again : they may have pencilled this last game of the season into their diaries as a chance to say goodbye to Trescothick, but found that it was to be the game that decided the Championship in favour of Essex, with only a cameo appearance from Trescothick, as a substitute fielder. It will not come as a surprise by now to learn that Hamilton provides a fuller account of the game. Henderson prefers to trace a line of Somerset melancholy (not a quality that I associate with that county) from John Cowper Powys to Trescothick, via Gimblett, Robertson-Glasgow, Roebuck (‘a pervert’), Mark Lathwell and Alan Gibson. He signs off with a summary of the season which begins with a conversation he once had with Stephen Sondheim about Wallace Stevens, and ends with a celebration of Darren Stevens. All human life is there.

A ’Postlude’ finds him in Munich, which ‘works in ways which should make Britons envious’, in search of ‘a cleansing week of paintings’. Henderson is the type of English patriot who would mostly prefer to be in another country (this sounds like a sneer, but is not : if I were to wake up tomorrow to find that I had been forcibly emigrated to Italy or Spain, I imagine that I should feel, at worst, ambivalent****). From there, he follows the draft for ‘The Hundred’ : which does not offer much incentive for him to return in time for the next English season.

If you have made it this far, you will have gathered that this is not an ideal Christmas present for the putative cricket-loving Dad whom we encountered in the first paragraph : he would, I think, much prefer to find Hamilton’s book in his stocking. The ideal recipient would probably be a bright, but uninformed, fourteen-year-old who knows nothing about the history of cricket, and holds ‘progressive’ views. He or she would learn a great deal about all manner of things, be treated to some funny stories and interesting facts, and might even be led to reconsider some of their preconceptions (but that is, of course, the last type of person who will ever read it).

The book ends with another line of Larkin’s : ‘We should be kind, while there is still time’. Kindness has not always been the most obvious characteristic of Henderson’s journalism, but, for someone who has made a career out of being disagreeable, this is a strangely agreeable book (and not only in the Wallace Arnold sense). He acknowledges that a large part of his hostility to aspects of contemporary cricket is a matter of age (to recap, he is a year older than Hamilton, and two years older than me) : (of ‘the Hundred’) ‘it is a generational thing, and age helps determine taste’ ; (at the T20) ‘‘Doubt, or age, simply?’ Age. The younger spectators have few doubts’. The end of the main body of the text is conciliatory and resigned :

‘The boat heading for the new world awaits, rigged and masted. All we can do is hand the game on, and hope those eager to remake it in a manner of their choosing acknowledge we did our best. If we promise to be good they may even wave to us.’

He has, by his own account, led a full and happy life, and the best of his book is a celebration of that life. Hamilton seems genuinely heartbroken about the expected demise of long-form cricket, but then I have the impression that it is much closer to his heart than it is to Henderson’s, who has so much else to occupy him. Henderson, like Larkin, just thinks it will happen, soon.

*‘The Agreeable World of Wallace Arnold’, for younger readers (if any), was an affectionate parody of an old-school Spectator columnist, by Craig Brown. Wallace was much given to complaining about modern innovations, such as the ‘annoying ts ts leaking from a ‘personal stereo’ (dread phrase!)’, and recounting the agreeable lunches he had enjoyed with various, sometimes unlikely, ‘old chums and quaffing partners’. I suspect that he has now followed his models into extinction.

**Only one baronetcy has been created since 1965, for Denis Thatcher. Botham has, arguably, done better than that since.

***An unacknowledged quotation from Henry Mancini’s ‘Days of Wine and Roses’.

****Less likely than ever to happen now. One of the many demerits of leaving the European Union is that it stimulates the desire to emigrate, while making it harder to satisfy that desire.